The Chinese economy is in the doldrums. Its property market is a huge heap of failure, spreading trouble to the country’s lenders and heavily indebted local governments. The Chinese consumers, who were expected to lift global demand, are downbeat; the sharp rise in youth unemployment isn’t helping. Chinese imports have tumbled, while exports, once a robust engine of growth, are in decline. The country is registering a drop in prices, adding to signs of a significant economic slowdown. The Chinese stocks have fallen to a fraction of their value three years ago, spurring some investors to search for value. But will Chinese stocks rebound and reward their investors?

Claim 50% Off TipRanks Premium

- Unlock hedge fund-level data and powerful investing tools for smarter, sharper decisions

- Stay ahead of the market with the latest news and analysis and maximize your portfolio's potential

Chinese Stocks Humbled

2023 was meant to be the year of Chinese stocks. As the country emerged from the world’s strictest and longest Covid-19 restrictions, its economy was expected to roar back, and its consumers, free at last, were expected to go on a spending spree, powering local and global business activity. Sell-side analysts were busy selling the China rebound narrative, which was gladly bought by asset managers around the world. It wouldn’t be fair to blame them, though, as the high-growth years before the pandemic have created a strong “conditioned reflex” to believe in superior vitality of the Red Dragon’s economy.

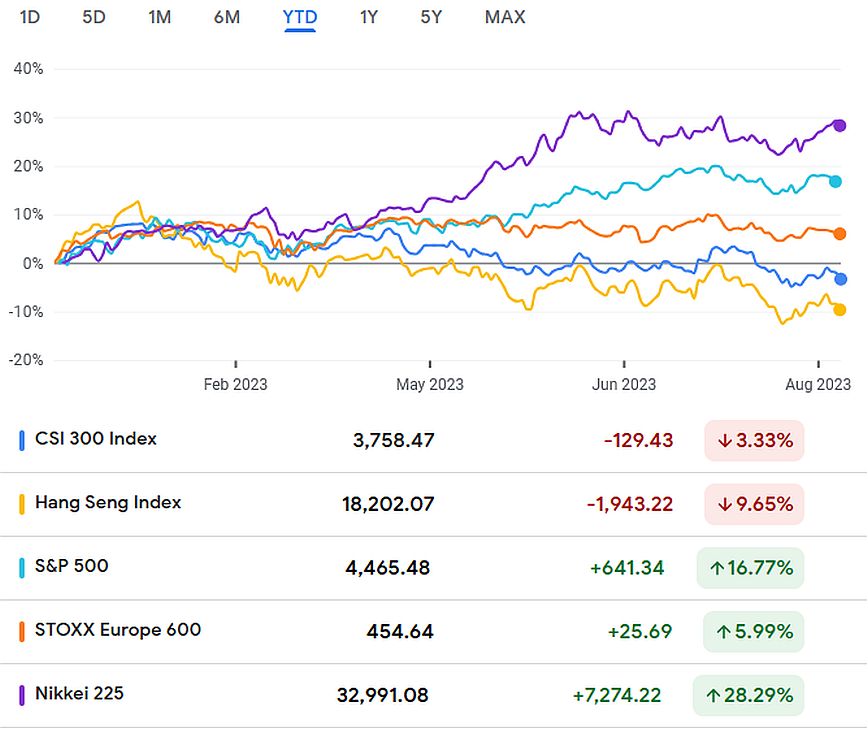

The CSI 300, an index of top-300 mainland shares, and the Hang Seng, an index of Chinese stocks traded in Hong Kong, surged from their November lows to their latest high in January, from which they fell… and fell… and fell more. Their strong divergence from the U.S. and global stocks should humble analysts that predicted double-digit returns for Chinese stocks this year.

Source: Google Finance

Morgan Stanley (MS) lowered its price target for all Chinese stock indexes, after slashing the country’s economic outlook. Similar moves were also made by other prominent global investment managers, such as Goldman Sachs (GS), Nomura (NMR), Barclays (BCS), and others.

Meanwhile, foreign investors continued to dump Chinese shares, with outflows accelerating in August to a record $12.5 billion. Growing tensions between the U.S. and China over trade and technology, as well as the concerns about worsening of the Chinese economic situation, are diminishing investors’ appetite for the country’s stock sector.

Chinese equity ETFs strongly underperformed their U.S.-equity centered peers. iShares MSCI China ETF (MCHI) is down 7.5% this year, versus an increase of 17% in its U.S. counterpart, SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust (SPY). The difference is even more glaring in tech stocks: while Nasdaq-following Invesco QQQ Trust Series (QQQ) is up 41% year-to-date, its Chinese twin, the Invesco China Technology ETF (CQQQ), is down by over 12%.

House of Cards

One of the hottest trouble spots in Chinese economy is the real estate market. The country’s property sector, which in the past added a large chunk to growth figures, is now a serious threat to the economy. The government’s attempts to restrain the quick build-up in debt of real estate developers resulted in a snowball effect of collapsing land and house sales, declining prices, developer bankruptcies, and defaults on mortgages and loans. Local governments, which became accustomed to windfall revenues from land sales, found themselves with empty coffers and humongous debt loads when this source of income dwindled. Apparently, local governments’ troubles with repaying their liabilities are a direct threat to Chinese regional and local banks.

The central government announced some measures “to boost the economy,” but, in truth, they can’t do much because the country is too indebted on all levels: total government, corporate, and household debt stands at around 280% of GDP. And that’s only the debts that are on the books; analysts estimate that local government debt channeled through separate financial vehicles is as large as the “official” one, if not larger.

Adding government stimulus could jolt economic growth for a short while, but seriously exacerbate debt risks in the longer run. Besides, China has seen diminishing returns on its investments, partly because of the recent years’ Beijing policies, which are best described as creeping nationalization. The current government under Xi Jinping has been busy unrolling the economic independence of the private sector, strengthening the party’s control over the economy. That, of course, has worsened the country’s productivity and weighed on private investment and hiring.

“Something is Rotten in the State of China”

All those problems come on top of the existing structural challenges within the economy, such as population aging and a shrinking labor force. There are additional troubles, some of which, like the property bust, can be blamed on government intervention. Thus, Beijing’s crackdown on tech and internet firms or whole sub-industries still reverberates through slower private investment growth and lower foreign investment in Chinese businesses as a whole.

Complicating the picture is the weak external demand, weighing on exports that have been one of the main drivers of growth, as well as an ongoing technological rivalry with the West, depressing imports and putting a strain on the country’s tech sector. The now-expected weaker growth leads to consumer expectations of higher unemployment and lower incomes, while falling home prices lead to a negative wealth effect. These factors are behind sluggish consumption; previously, consumption was one of the growth engines of the economy.

On top of all that, signs of deflation are becoming more prevalent, with the decline in prices depressing the incentive to invest and spend and increasing the value of debts. If deflation becomes entrenched while structural and other challenges are not addressed, China could fall into stagnation. Despite the deteriorating economic fundamentals already very apparent, there’s no threat of a wide economic crisis as of now, but whether the current trouble is temporary or a beginning of a downward spiral, only time will tell.

Will Tech Save the Communist Party?

Apparently, the Chinese authorities have realized that they are now between a rock and a hard place. The communist party’s rhetoric has long been based on China’s successful economic development as a proof of correctness, integrity, and wisdom of their policies. Now, they have to search for creative ways to spur growth before it’s too late.

Thus, Beijing has lately been signaling to the Chinese technology sector, and particularly to the owners and managers of leading tech companies like Tencent (TCEHY) and Alibaba (BABA), that they aren’t “enemies of the State” anymore, but heroes on a mission to save the economy. Government officials promised policy support, and loosened restrictions on the burgeoning generative artificial intelligence (Gen AI) industry to allow competition with the U.S. tech firms. How this competition is going to work out with the U.S. restrictions on chip exports to China and on active investments in the country’s tech firms, is unclear.

Besides, once burned, investors in Chinese firms will not easily forget the government’s earlier heavy-handed approach towards private enterprises. These included eliminating the whole online education industry, forcing Ant Group’s IPO suspension, slapping heavy fines on Chinese leading tech companies for different “violations,” and many more actions that caused Western investors to reassess their sentiment towards Chinese stocks, including those traded in the U.S.

China Shrinks on the U.S. Exchanges

About 250 Chinese companies are now listed on the U.S. stock exchanges, either through American Depositary Receipts (ADRs) or directly (through common stock issued in the U.S.). Ten largest of them by market cap are Tencent Holdings (TCEHY), Alibaba (BABA), Pinduoduo (PDD), NetEase (NTES), JD.com (JD), Baidu (BIDU), Li Auto (LI), Yum China Holdings (YUMC), Trip.com (TCOM), BeiGene (BGNE), and KE Holdings (BEKE). There are also well-known names like ZTO (ZTO), NIO (NIO), DiDi Global (DIDI), MINISO (MNSO), Weibo (WB), Agora (API), and others. Most of them are bundled under the general ticker “internet companies” – they are the acting or aspiring Amazons, Googles, Facebooks, WhatsApps, Ubers, Activision Blizzards, or Booking.coms of China.

The total market capitalization of the Chinese companies trading in the U.S. currently stands at $845 billion, down from $1 trillion in the beginning of the year, and a far cry from their peak of $2.11 trillion in May 2021. The decline in the U.S.-listed companies’ market size comes on the back of both the fall in their share prices, and the delisting of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) which didn’t (or weren’t allowed to) disclose their financial audits for inspection.

Weighing Opportunities and Risks

The performance of the Chinese stocks in the U.S. has been uneven this year. While Tencent and Alibaba have mostly traded sideways around the zero line, Baidu has shown a positive, if volatile, trend, and Weibo tumbled. All in all, the S&P China ADR Index, which tracks Chinese ADRs’ performance on the U.S. exchanges, has strongly underperformed the S&P 500 (SPX) this year, with the Chinese index bobbing around 0% while the SPX is up 17%.

However, the underperformance didn’t start on January 1st; it has been present ever since Chinese President Xi Jinping intensified his crackdown on the private sector through a slew of regulatory action against the country’s tech companies in 2021. Their attempt at recovery at the end of last year, spurred by the reopening hopes, faded at the signs of China economy’s weakening.

Source: Google Finance

While the slump in Chinese stock price has excited some value-seeking money managers, most are treading with caution. After all, the fate of Chinese companies, whether traded in the U.S. or not, depends on the country’s economic growth, as well as on its rulers’ good will.

The economic picture is the easier one to decipher and forecast. China’s momentum seems to be waning; it now faces multiple challenges, preventing it from returning to the past decade’s double-digit growth. However, the giant is weakened, not fallen. The country is still expected to grow at an average annual rate of 5% in the next years, a clip that would exhilarate any developed economy. Its population of 1.5 trillion, of which about 400 million belong to the high-consumption middle-income group, isn’t easy to ignore. Even in a slowing economy, the vast consumer base, known for its wide technological adoption, still presents an enormous “feeding ground” for Chinese companies. They may not continue growing their earnings as fast as they did before the pandemic, but they will still be able to grow and prosper… if the Communist party allows.

The main risk to the Chinese stocks is political. Yes, now the authorities try to play up to the tech tycoons, but that may change at any moment. The whims of the ruling party in China are unpredictable; as we have seen on numerous occasions, in the end, political causes in China strongly prevail over economic reason.